Last month, while Massachusetts endured a gray, chilly January, I found myself deep in the Liberian rainforest. With a colleague from the University of Georgia (UGA), I visited two forest-dependent communities in the Liberian interior, and spoke with a wide variety of people there about their needs, challenges, expertise, and aspirations.

The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) has awarded $5 million to a team of institutions, led by UGA, to implement a program called Higher Education for Conservation Activity (HECA) in Liberia. Its purpose is to develop a bigger, stronger conservation-oriented forestry workforce there. WCW is one of these participating institutions, and this is our first project in the environmental arena.

Liberia is a country I have been working in since 2009, mostly in the gender and higher ed arenas. This project is actually no different, because WCW’s role is to coordinate the aspects related to gender equality and social inclusion: We want more women in this forestry workforce, and more of other kinds of people who have historically been excluded or sidelined. We also want this project to empower youth, because more than 60% of Liberia’s population is under 25.

Saving the rainforest means less climate migration, less violent extremism, and lower risk of resource wars. It also means fewer mental health crises, and fewer gender-based violence war crimes such as the rape and abduction of women, especially young women and girls.

Why does USAID care about forestry in Liberia, and why does WCW? Well, the timing of this project comes at a tipping point for Liberia’s rainforests, which account for approximately half of the remaining rainforests in West Africa. Over many years, these forests have been degraded by unsustainable forestry practices, land conversion, and other pressures.

We know that rainforests are the lungs of the planet and reservoirs of biodiversity. But when they dry up and turn to desert—as has happened in Chad, Mali, Burkina Faso, and the Central African Republic over the past half century—social, economic, and political disasters result as well. These include resource shortages (most notably water), political instability, jihadist incursions, lawlessness, violence, and climate migration. Reducing these is a goal of U.S. foreign policy. Saving the rainforest means less climate migration, less violent extremism, and lower risk of resource wars. It also means fewer mental health crises, and fewer gender-based violence war crimes such as the rape and abduction of women, especially young women and girls.

That’s why it is a vital part of HECA and WCW’s mission to design a strategy to empower women and young people in the Liberian forestry sector: When rainforests disappear, they are directly affected, so they must be part of the solution. This strategy will also benefit people with disabilities, crisis- and conflict-affected individuals, first-generation post-secondary students, people from minority religious communities, and rural, forest-dwelling, and forest-dependent people. HECA is built on the premise that sustainable development must be inclusive development.

Our team spent December and January getting the project off the ground in Liberia, meeting with USAID, our colleagues at the Liberian partner institutions, and a diverse array of stakeholders in government, local communities, and the NGO sector. A highlight of the trip was conducting a three-day social science research methods training workshop with student interns at the Liberian Forestry Training Institute who will be collecting data.

I’m looking forward to returning to Liberia for two weeks in March to meet with the data collectors and work with another set of UGA colleagues who are coming to the country for the first time. And I will return again in August to present at a larger convening. After that, I expect to return to Liberia periodically as the team works on creating a thriving forestry workforce that has the knowledge to conserve Liberian natural resources—and that includes those whose lives are directly affected by environmental sustainability. What an exciting new venture for WCW!

Layli Maparyan, Ph.D., is the Katherine Stone Kaufmann ’67 Executive Director of the Wellesley Centers for Women.

Critical race theory has become the latest front in the culture wars. Depending on what you’ve read or what you’ve heard from politicians, you may be under the impression that critical race theory means talking about racism in any context, or that it means white people are inherently racist.

Critical race theory has become the latest front in the culture wars. Depending on what you’ve read or what you’ve heard from politicians, you may be under the impression that critical race theory means talking about racism in any context, or that it means white people are inherently racist.

We at the Wellesley Centers for Women are starting our week with a sense of hope and possibility. We are proud to have a new

We at the Wellesley Centers for Women are starting our week with a sense of hope and possibility. We are proud to have a new

The callous killing of

The callous killing of  During this unprecedented time, our work at the Wellesley Centers for Women towards gender equality, social justice, and human wellbeing has taken on new meaning. As a society, we have become newly aware of just how fragile and precious human wellbeing is. And as an organization, we have been reminded of how deeply we care about the physical and mental wellbeing of our community — our research scientists, project directors, administrative staff, and supporters like you — as well as the larger global community to which we all belong.

During this unprecedented time, our work at the Wellesley Centers for Women towards gender equality, social justice, and human wellbeing has taken on new meaning. As a society, we have become newly aware of just how fragile and precious human wellbeing is. And as an organization, we have been reminded of how deeply we care about the physical and mental wellbeing of our community — our research scientists, project directors, administrative staff, and supporters like you — as well as the larger global community to which we all belong. The long march towards progress is often one that extends across generations. The U.S.

The long march towards progress is often one that extends across generations. The U.S.  This week, Canada launched the

This week, Canada launched the  Recently I returned from Liberia, which USA Today just rated as

Recently I returned from Liberia, which USA Today just rated as  Another view—one that I would like to align with the research and action of the Wellesley Centers for Women—is one that sees (and contributes to) hope, promise, and enthusiasm in and with regard to African youth and their prospects. An approach that asks African youth for their own perspectives and aspirations, one that embraces African youth and their insights and talents, and one that takes the historical, political, economic, structural, and systemic context of African youths’ lives into consideration—and, at times, challenges those—is the one I would like not only to endorse, but to operationalize. It is an approach that sees the wealth in people, not just one that sees the poverty created by their circumstances. It is also an approach that cultivates African youth leadership.

Another view—one that I would like to align with the research and action of the Wellesley Centers for Women—is one that sees (and contributes to) hope, promise, and enthusiasm in and with regard to African youth and their prospects. An approach that asks African youth for their own perspectives and aspirations, one that embraces African youth and their insights and talents, and one that takes the historical, political, economic, structural, and systemic context of African youths’ lives into consideration—and, at times, challenges those—is the one I would like not only to endorse, but to operationalize. It is an approach that sees the wealth in people, not just one that sees the poverty created by their circumstances. It is also an approach that cultivates African youth leadership. Thich Nhat Hanh, the Vietnamese Buddhist monk nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1967, famously characterized the human mind as a storehouse filled with two kinds of seeds: good and bad. Humans have the capacity to be both good and evil, he pointed out, and it’s the seeds we water that ultimately grow. Think about that. When we look around the world today, we see a lot of evil sprouting up all around, and we wonder where it came from. We scratch our heads, we point fingers, and sometimes, in frustration, we join in the fray. Based on Thich Nhat Hanh’s insight, we should really take a closer look at how we are watering the seeds of the very evils we decry and detest – incivility, hate-based conflict and violence, and even basic intolerance.

Thich Nhat Hanh, the Vietnamese Buddhist monk nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1967, famously characterized the human mind as a storehouse filled with two kinds of seeds: good and bad. Humans have the capacity to be both good and evil, he pointed out, and it’s the seeds we water that ultimately grow. Think about that. When we look around the world today, we see a lot of evil sprouting up all around, and we wonder where it came from. We scratch our heads, we point fingers, and sometimes, in frustration, we join in the fray. Based on Thich Nhat Hanh’s insight, we should really take a closer look at how we are watering the seeds of the very evils we decry and detest – incivility, hate-based conflict and violence, and even basic intolerance. , Ph.D., is the Katherine Stone Kaufmann ’67 Executive Director of the

, Ph.D., is the Katherine Stone Kaufmann ’67 Executive Director of the  This week, the

This week, the

The biggest gift I can offer at this time is empathy – to those whose hopes were shattered, to those whose anger, pain, and frustration led us in this surprising direction, and to those who are just plain terrified right now, especially the little ones and the youth. Clearly, we are a country of different realities, and we need to find common ground. I remind myself of my own mantra, “All of us are sacred.” As Thich Nhat Hanh taught me, I breathe in, breathe out, and utilize the present moment as a place of refuge.

The biggest gift I can offer at this time is empathy – to those whose hopes were shattered, to those whose anger, pain, and frustration led us in this surprising direction, and to those who are just plain terrified right now, especially the little ones and the youth. Clearly, we are a country of different realities, and we need to find common ground. I remind myself of my own mantra, “All of us are sacred.” As Thich Nhat Hanh taught me, I breathe in, breathe out, and utilize the present moment as a place of refuge. Since voting this morning, all I have been able to think about is the next four years. Without even knowing yet who is going to win, my mind has already jumped ahead. What do we want the next four years to be like? What can we do to make them be the way we want them to be? The negativity of the last 18 months has been excruciating, and I know it doesn’t represent the best of who we are. I want better for all of us!

Since voting this morning, all I have been able to think about is the next four years. Without even knowing yet who is going to win, my mind has already jumped ahead. What do we want the next four years to be like? What can we do to make them be the way we want them to be? The negativity of the last 18 months has been excruciating, and I know it doesn’t represent the best of who we are. I want better for all of us! I’m starting with a post-election community unity block party in my neighborhood. I’m inviting the people I see every day – and a few I’ve yet to see, since I’m new to my neighborhood – to my home for an evening of fellowship and food with my family. I’ve let everyone know that it doesn’t matter how you voted, where you worship, whom you love, or where you come from – I just want us to come together in the spirit of friendship and community. My hope is that we will affirm each other as neighbors, discover through conversation the wonders of our diversity, and deepen our sense of connection, concern, and shared destiny. Maybe you can do something like this on the block where you live, too.

I’m starting with a post-election community unity block party in my neighborhood. I’m inviting the people I see every day – and a few I’ve yet to see, since I’m new to my neighborhood – to my home for an evening of fellowship and food with my family. I’ve let everyone know that it doesn’t matter how you voted, where you worship, whom you love, or where you come from – I just want us to come together in the spirit of friendship and community. My hope is that we will affirm each other as neighbors, discover through conversation the wonders of our diversity, and deepen our sense of connection, concern, and shared destiny. Maybe you can do something like this on the block where you live, too.

When the U.S. Department of the Treasury announced two years ago that it was planning to put a woman on the $10 bill, I voted for Harriet Tubman every chance I got. I was privileged to participate in an invitation-only phone call of women leaders with representatives from the Treasury Department, and I also voted online as an “ordinary citizen.” And I unapologetically urged my friends on social media to do the same. So, when the

When the U.S. Department of the Treasury announced two years ago that it was planning to put a woman on the $10 bill, I voted for Harriet Tubman every chance I got. I was privileged to participate in an invitation-only phone call of women leaders with representatives from the Treasury Department, and I also voted online as an “ordinary citizen.” And I unapologetically urged my friends on social media to do the same. So, when the  Admittedly, if I had a private audience with Secretary Lew, I would suggest the inclusion of some notable Americans of Asian, Latin, Middle Eastern, Native American, and Pacific Islander descent in addition to the very welcome inclusion of African Americans on the new bills--and I might even suggest that he replace the image of slaveholder President Andrew Jackson (after whom my hometown, Jacksonville, Florida, is named, incidentally) with these diverse Americans, since he has (too) long had his day in the sun. I can only hope that this is the plan for the $50 and $100 bills!

Admittedly, if I had a private audience with Secretary Lew, I would suggest the inclusion of some notable Americans of Asian, Latin, Middle Eastern, Native American, and Pacific Islander descent in addition to the very welcome inclusion of African Americans on the new bills--and I might even suggest that he replace the image of slaveholder President Andrew Jackson (after whom my hometown, Jacksonville, Florida, is named, incidentally) with these diverse Americans, since he has (too) long had his day in the sun. I can only hope that this is the plan for the $50 and $100 bills!

market women organizations, with a special focus on gender parity in leadership. Although women are, by far, the largest proportion of marketers and traders, often it is the few men who are afforded positions of leadership that allow them to engage with policymakers. The market women who participated in our study would like to see women’s voices rise to the top and for women’s leadership to be recognized with top-level posts. Additionally, they indicated that the time might be right for a West Africa-wide market women’s organization that allowed market women from different countries to network, share best practices, and shape policy that affects them. Many touted the Sirleaf Market Women’s Fund as a good example of a multi-constituency organization that has raised the visibility of market women’s issues at the same time as it has brought different stakeholders together for a common cause, and they imagined this model growing from its roots in Liberia to other countries. Additionally, the pivotal roles of the African Women’s Development Fund, UN Women, and Ford, all of which have provided funding for market women’s issues and related actions, were lauded as model donors.

market women organizations, with a special focus on gender parity in leadership. Although women are, by far, the largest proportion of marketers and traders, often it is the few men who are afforded positions of leadership that allow them to engage with policymakers. The market women who participated in our study would like to see women’s voices rise to the top and for women’s leadership to be recognized with top-level posts. Additionally, they indicated that the time might be right for a West Africa-wide market women’s organization that allowed market women from different countries to network, share best practices, and shape policy that affects them. Many touted the Sirleaf Market Women’s Fund as a good example of a multi-constituency organization that has raised the visibility of market women’s issues at the same time as it has brought different stakeholders together for a common cause, and they imagined this model growing from its roots in Liberia to other countries. Additionally, the pivotal roles of the African Women’s Development Fund, UN Women, and Ford, all of which have provided funding for market women’s issues and related actions, were lauded as model donors.

One conundrum that was discussed is the fact gender-based violence statistics have gone up in recent years in Ghana, begging the question of whether domestic violence really is on the rise or, alternately, whether the new law has merely increased reporting of incidents due to society-wide sensitization. Although both factors may be at play, there was general agreement that the law was a necessary intervention on an unacceptable situation--broad scale gender-based violence in Ghana. (Of course, lest anyone single Ghana out, the

One conundrum that was discussed is the fact gender-based violence statistics have gone up in recent years in Ghana, begging the question of whether domestic violence really is on the rise or, alternately, whether the new law has merely increased reporting of incidents due to society-wide sensitization. Although both factors may be at play, there was general agreement that the law was a necessary intervention on an unacceptable situation--broad scale gender-based violence in Ghana. (Of course, lest anyone single Ghana out, the

data, convened a group of stakeholders to write new policy, and shepherded the draft policy through the national legislative process while simultaneously engaging in public education so that the government and the people were in it together. They needed to piece together support from many sources over many years to make this happen. Many others who also cared passionately about ending gender-based violence worked with them or supported this work. Now, as Ghana looks ahead the tenth anniversary of its landmark domestic violence legislation, the country can claim many accomplishments. These include the expansion of its judiciary system to address gender-based violence, a sensitized police force that includes a domestic violence unit, and the leadership of its Ministry of Gender, Children, and Social Protection. It also includes increased awareness of groups with special vulnerabilities (such as people with disabilities), and the education and sensitization efforts of numerous NGOs like WiLDAF and academic institutes like CEGENSA. All of these actors are vigorously working together to make sure that the country as a whole is moving in the same direction--away from gender-based violence and towards peace and security for women. Other countries can learn from Ghana --and other countries can increase the link between research and action to end gender-based violence.

data, convened a group of stakeholders to write new policy, and shepherded the draft policy through the national legislative process while simultaneously engaging in public education so that the government and the people were in it together. They needed to piece together support from many sources over many years to make this happen. Many others who also cared passionately about ending gender-based violence worked with them or supported this work. Now, as Ghana looks ahead the tenth anniversary of its landmark domestic violence legislation, the country can claim many accomplishments. These include the expansion of its judiciary system to address gender-based violence, a sensitized police force that includes a domestic violence unit, and the leadership of its Ministry of Gender, Children, and Social Protection. It also includes increased awareness of groups with special vulnerabilities (such as people with disabilities), and the education and sensitization efforts of numerous NGOs like WiLDAF and academic institutes like CEGENSA. All of these actors are vigorously working together to make sure that the country as a whole is moving in the same direction--away from gender-based violence and towards peace and security for women. Other countries can learn from Ghana --and other countries can increase the link between research and action to end gender-based violence.

Beatrice’s education. As a result, Beatrice made it all the way to

Beatrice’s education. As a result, Beatrice made it all the way to  Recently, Beatrice updated us about her activities, which have grown to support the communities where she works in even broader ways. In addition to a library/community center in Amor Village, which was her project under IREX, she has now started a school complex in Tororo village that already includes a primary school and will grow to include a nursery school, a secondary school, and a vocational education center. Twenty-seven of the mentees who started with PCEF/RGCM at the beginning of secondary school are now pursuing university education. About half of them are studying to become teachers, but the others are pursing fields as diverse as accounting and finance, adult education, economics, motor mechanics, clinical medicine, nursing, human resource management, and wildlife management. Finally, Beatrice is mobilizing donors to purchase solar panels for the families in her network so that they can stop using kerosene lamps. She just thinks of everything!

Recently, Beatrice updated us about her activities, which have grown to support the communities where she works in even broader ways. In addition to a library/community center in Amor Village, which was her project under IREX, she has now started a school complex in Tororo village that already includes a primary school and will grow to include a nursery school, a secondary school, and a vocational education center. Twenty-seven of the mentees who started with PCEF/RGCM at the beginning of secondary school are now pursuing university education. About half of them are studying to become teachers, but the others are pursing fields as diverse as accounting and finance, adult education, economics, motor mechanics, clinical medicine, nursing, human resource management, and wildlife management. Finally, Beatrice is mobilizing donors to purchase solar panels for the families in her network so that they can stop using kerosene lamps. She just thinks of everything!

Over the summer, Alan visited us here at the Wellesley Centers for Women, and here’s what he had to say about Maggie>>

Over the summer, Alan visited us here at the Wellesley Centers for Women, and here’s what he had to say about Maggie>>

In the mid-1970s, Stanford-based psychologist

In the mid-1970s, Stanford-based psychologist

ck History Month, which began as Negro History Week in 1926. He was an erudite and meticulous scholar who obtained his B.Litt. from Berea College, his M.A. from the University of Chicago, and his doctorate from Harvard University at a time when the pursuit of higher education was extremely fraught for African Americans. Because he made it his mission to collect, compile, and distribute historical data about Black people in America, I like to call him “the original #BlackLivesMatter guy.” His self-declared dual mission was to make sure the African-Americans knew their history and to insure the place of Black history in mainstream U.S. history. This was long before Black history was considered relevant, even thinkable, by most white scholars and the white academy. In fact, he writes in the preface of The Negro in Our History that he penned the book for schoolteachers so that Black history could be taught in schools—and this, just in time for the opening of Washington High School.

ck History Month, which began as Negro History Week in 1926. He was an erudite and meticulous scholar who obtained his B.Litt. from Berea College, his M.A. from the University of Chicago, and his doctorate from Harvard University at a time when the pursuit of higher education was extremely fraught for African Americans. Because he made it his mission to collect, compile, and distribute historical data about Black people in America, I like to call him “the original #BlackLivesMatter guy.” His self-declared dual mission was to make sure the African-Americans knew their history and to insure the place of Black history in mainstream U.S. history. This was long before Black history was considered relevant, even thinkable, by most white scholars and the white academy. In fact, he writes in the preface of The Negro in Our History that he penned the book for schoolteachers so that Black history could be taught in schools—and this, just in time for the opening of Washington High School. women. It enlivens my curiosity to imagine my grandmother Jannie as a young woman learning in school about her own history from Carter G. Woodson’s text, which, at that time was still relatively new, alongside anything else she might have been learning. It saddens me to reflect on the fact that my own post-desegregation high school education, AP History and all, offered no such in-depth overview of Black history, African American or African.

women. It enlivens my curiosity to imagine my grandmother Jannie as a young woman learning in school about her own history from Carter G. Woodson’s text, which, at that time was still relatively new, alongside anything else she might have been learning. It saddens me to reflect on the fact that my own post-desegregation high school education, AP History and all, offered no such in-depth overview of Black history, African American or African. After finishing high school, my grandmother Jannie, like many of her generation, worked as a domestic for many years. However, after spending time working in the home of a doctor, she was encouraged and went on to become a licensed practical nurse (LPN), which took two more years of night school. From that point until her death, she worked as a private nurse to aging wealthy Atlantans. This enabled her to make a good, albeit humble, livelihood for herself and her two daughters, along with my great grandmother Laura, who lived with her and served as her primary source of childcare, particularly after her brief marriage to my grandfather, an older man who she found to be overbearing, ended. With this livelihood, she was able to put both her daughters through Spelman College, the nation’s leading African American women’s college, then and now. It stands as a point of pride to our whole family that, although she was unable to attend due to family responsibilities, Jannie herself was also at one time admitted to

After finishing high school, my grandmother Jannie, like many of her generation, worked as a domestic for many years. However, after spending time working in the home of a doctor, she was encouraged and went on to become a licensed practical nurse (LPN), which took two more years of night school. From that point until her death, she worked as a private nurse to aging wealthy Atlantans. This enabled her to make a good, albeit humble, livelihood for herself and her two daughters, along with my great grandmother Laura, who lived with her and served as her primary source of childcare, particularly after her brief marriage to my grandfather, an older man who she found to be overbearing, ended. With this livelihood, she was able to put both her daughters through Spelman College, the nation’s leading African American women’s college, then and now. It stands as a point of pride to our whole family that, although she was unable to attend due to family responsibilities, Jannie herself was also at one time admitted to  ge. Sadly, she didn’t live to see me attain my Ph.D., but, when she passed away, I was already pursuing my Masters degree, and, like her, I was also mother to a second child. Thus, when I inherited The Negro in Our History, it was more than a quaint artifact of an earlier era, and more than just a physical symbol of Black History Month. Rather, it was where Black history, women’s history, the pursuit of education, the pursuit of social justice, my own history, and my own destiny met.

ge. Sadly, she didn’t live to see me attain my Ph.D., but, when she passed away, I was already pursuing my Masters degree, and, like her, I was also mother to a second child. Thus, when I inherited The Negro in Our History, it was more than a quaint artifact of an earlier era, and more than just a physical symbol of Black History Month. Rather, it was where Black history, women’s history, the pursuit of education, the pursuit of social justice, my own history, and my own destiny met.

The story of

The story of

capital. It was witnessing homelessness in her city that inspired her to figure out how she and her family could make a real difference, and her “power of half” principle has since become a movement.

capital. It was witnessing homelessness in her city that inspired her to figure out how she and her family could make a real difference, and her “power of half” principle has since become a movement.

As an integral creative spirit within the Black Arts Movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s, Dr. Angelou’s works of autobiography then poetry helped lay the foundation for Black women’s literature and literary studies, as well as Black feminist and womanist activism today. By laying bare her story, she made it possible to talk publicly and politically about many women’s issues that we now address through organized social movements – rape, incest, child sexual abuse, commercial sexual exploitation, domestic violence, and intimate partner violence. Through the acknowledgement of lesbianism in her writings as well as her public friendship with Black gay writer and activist James Baldwin, she helped shift America’s ability to envision and enact civil rights advances for the LGBTQ community. And the time she spent in Ghana during the early 1960s (where she met W.E.B. DuBois and made friends with Malcolm X, among others), helped Americans of all colors draw connections between the civil rights and Black Power movements in the U.S. and the decolonial independence and Pan-African movements of Africa and the diaspora.

As an integral creative spirit within the Black Arts Movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s, Dr. Angelou’s works of autobiography then poetry helped lay the foundation for Black women’s literature and literary studies, as well as Black feminist and womanist activism today. By laying bare her story, she made it possible to talk publicly and politically about many women’s issues that we now address through organized social movements – rape, incest, child sexual abuse, commercial sexual exploitation, domestic violence, and intimate partner violence. Through the acknowledgement of lesbianism in her writings as well as her public friendship with Black gay writer and activist James Baldwin, she helped shift America’s ability to envision and enact civil rights advances for the LGBTQ community. And the time she spent in Ghana during the early 1960s (where she met W.E.B. DuBois and made friends with Malcolm X, among others), helped Americans of all colors draw connections between the civil rights and Black Power movements in the U.S. and the decolonial independence and Pan-African movements of Africa and the diaspora.

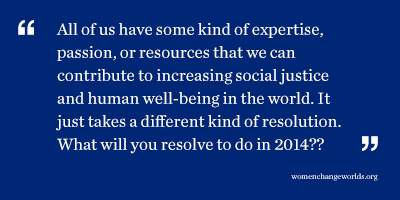

Just because we don’t all work for social change organizations, however, doesn’t mean there aren’t major ways we can make each a difference. What do you care about? What change would you like to see in the world? As great and necessary as organizations are in the social change equation, they are not the end-all and be-all. Individuals and small groups, even when they are working for change outside formal organizations, can make a monumental difference in outcomes for many through partnering, advocacy, endorsement, and financial support. As

Just because we don’t all work for social change organizations, however, doesn’t mean there aren’t major ways we can make each a difference. What do you care about? What change would you like to see in the world? As great and necessary as organizations are in the social change equation, they are not the end-all and be-all. Individuals and small groups, even when they are working for change outside formal organizations, can make a monumental difference in outcomes for many through partnering, advocacy, endorsement, and financial support. As  Part II: Social Scientific Perspectives on Making Change in America

Part II: Social Scientific Perspectives on Making Change in America Depression is more epidemic than the common cold, and we hear more and more about such issues as bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicide. On the one hand, we have begun to recognize a connection between mental ibellness and certain forms of violence – and while mental illness certainly doesn’t explain all forms of violence in America, it raises our level of concern about why people experience mental illness and whether we are doing enough about it. Fortunately, the Affordable Care Act will make

Depression is more epidemic than the common cold, and we hear more and more about such issues as bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicide. On the one hand, we have begun to recognize a connection between mental ibellness and certain forms of violence – and while mental illness certainly doesn’t explain all forms of violence in America, it raises our level of concern about why people experience mental illness and whether we are doing enough about it. Fortunately, the Affordable Care Act will make

During the flight home, as I reviewed the day’s

During the flight home, as I reviewed the day’s

life-changing impact of our own

life-changing impact of our own

pragmatic level, it was pointed out that the statistical apparatus which will make disaggregation of data possible on global or country-level indicators remains to be designed or put into place.

pragmatic level, it was pointed out that the statistical apparatus which will make disaggregation of data possible on global or country-level indicators remains to be designed or put into place.

eras cracking jokes at the expense of his wife and daughter, among other things – for probably the fifth or tenth time in my life, I thought, “When is Disney ever going to progress to gender equality (or racial equality, for that matter)?” As someone who grew up in Florida, I love Disney World, and my point is simply some of the sources of violence in our society are “hidden in plain sight.”

eras cracking jokes at the expense of his wife and daughter, among other things – for probably the fifth or tenth time in my life, I thought, “When is Disney ever going to progress to gender equality (or racial equality, for that matter)?” As someone who grew up in Florida, I love Disney World, and my point is simply some of the sources of violence in our society are “hidden in plain sight.”

genuinely thankful, on behalf of all of those who came before in many generations, to establish this diverse nation and secure the rights of people of all genders and backgrounds to vote, for those who did exercise that right on Election Day. At the same time, I hope we recognize the need to elect ourselves as agents of change. Now, it is time to roll up our sleeves and get back to work–perhaps with even greater exuberance.

genuinely thankful, on behalf of all of those who came before in many generations, to establish this diverse nation and secure the rights of people of all genders and backgrounds to vote, for those who did exercise that right on Election Day. At the same time, I hope we recognize the need to elect ourselves as agents of change. Now, it is time to roll up our sleeves and get back to work–perhaps with even greater exuberance.

capital. It was witnessing homelessness in her city that inspired her to figure out how she and her family could make a real difference, and her “power of half” principle has since become a movement.

capital. It was witnessing homelessness in her city that inspired her to figure out how she and her family could make a real difference, and her “power of half” principle has since become a movement.