With a collection of government stamps in hand, I now needed to secure the tribal backing for the project. Government approval merely made my NGO official, but without the tribal endorsement, my effort to educate girls would be just another import with a short shelf life.

With a collection of government stamps in hand, I now needed to secure the tribal backing for the project. Government approval merely made my NGO official, but without the tribal endorsement, my effort to educate girls would be just another import with a short shelf life.Community involvement was the only way to ensure a lasting change. Tribal life was the only constant in our lives for centuries and, if approached the right way, it didn’t have to stand in opposition to progress nor modernity. Being a closed system, it simply required a change from within, a change that was a result of reckoning, not dictated or imposed. I thought I was well-placed to start the ball rolling. I belonged to the tribal system; I wasn’t an outsider trying to prove it wrong. If anything, I wanted to prove that the outside world was wrong about us and challenge the perception that rural areas are populated with people who stayed illiterate by choice. I knew firsthand that wasn’t true. They wanted to learn. They didn’t lack the will; they lacked the way.

Trailing my father to tribal meetings my entire childhood came in handy. I could easily get access to the leaders. I didn’t know what to expect, but cockily, I thought I’d be ready for whatever questions come my way.

I went to see a tribal leader deep in the Kandahar Province as a litmus test. He received me at his home, and if he was uncertain about the purpose of my visit, he didn’t show it. This wrinkled, bearded man sitting across from me was probably the only person within a ten-mile radius who could read or write.

I was nervous for the first time. Ministry meetings made me defiant and angry; it was easy enough to forget about being nervous. Here, however, there was none of it. No hostility, nothing to get angry about. The stakes felt higher. My palms started sweating.

Tea was served, we exchanged pleasantries. I’m always proud when I manage not to anger anyone early in a conversation, so I saw that as a positive sign. I answered all his questions about my father’s well-being at length, and then I explained why I was there. “I know there is no girls' school in your village and there is no way for girls to get an education.” He nodded.

“I head an NGO”—saying those words out loud still felt strange—“and the idea is to make basic education available on tablets. I would like to use them here, in Kandahar Province. That way, girls could get an education even if they’re not able to go to school.”

I explained that none of it was imminent; I was still waiting for the tablets to be delivered. But when they were ready, I would like to distribute them in his village. From there, I launched into explaining the technical aspect of it all. “The tablets are solar-powered, and you don’t need the internet. Everything girls need is on the tablet already!” Over and over, I kept highlighting the ease of use.

I smiled as I finished with my presentation, ever so pleased with myself and my little speech. I thought it went well. It was clear and simple, informative without being condescending.

After a few seconds of silence, he asked a single question: “Why would girls need to be educated at all?”

With that, my smugness was gone.

The question wasn’t a loaded one. It was simple, to the point, and relevant to the conversation. I could feel my face turning red with embarrassment and felt a sudden desire to hide. The flight response was due to the horrifying realization that I didn’t know how to answer his question. To me, educating girls was about empowering them, but I knew very well that was not the argument I should offer to him. In his eyes, empowering girls was only half the answer and the less important half at that. It’s what Western organizations kept getting wrong about Afghanistan. We live and breathe as a community. Individuality matters less here than in the West. Advocating for special groups is often seen as somehow less holistic, as missing the point. It’s only half a pitch. If you’re changing the fabric of society, you need to prove that it’s for the good of the entire community. Here, the communal good reigns supreme.

I understood exactly what he meant when he asked the question, but I wasn’t entirely sure how to frame my arguments in response. My pitch, the one that I was so proud of until a few minutes ago, was worse than the government proposals. At least the government came armed with the tangible benefit of bribes. I had nothing. I came to the fight unable to defend the very premise. I didn’t even know how to defend education itself, not for girls, not for boys. The need for it was drummed into me, first by my own family, then by the school. It was not something I ever had to formulate before. I knew instinctively that education was necessary, but knowing something instinctively is a poor starting point in a debate.

The only answers I had at the ready were those offered by my Western education, peddling degrees and advocating along the lines of furthering your career choices, which, seriously, isn’t going to fly in rural Kandahar. I needed to defend getting educated as a concept not as a tool, and present education as a path not as a destination. Years of working toward this conversation, and I still wasn’t sure what to say. I was devastated. How did I miss that?

I faced a choice. I could try to talk my way out of it. I could offer platitudes and generic answers like a kid on an exam she didn’t prepare for. Or I could acknowledge that his question was too important to wing it, admit my failure, go back to the drawing board, and figure out the actual answer. I knew walking away could easily end the conversation altogether; yet insulting him with half-baked answers somehow seemed far worse. Leaving would at least show respect, something that my little speech was apparently sorrily lacking.

I mumbled that I’d get back to him.

It took me two months to prepare the answer. I searched for religious, cultural, and practical arguments. It was my mother who trained me for this moment with her skepticism, with her cross-examination of every decision I’ve ever made in life. Debate clubs have nothing on a Pashtun mother hurling chaplaks at you whenever you get the answer wrong. Chaplaks significantly improve your critical-thinking abilities.

When I finally went back to see him, I quickly skipped over the pleasantries. Yes, my father was still doing well. There was no need to get into it. I was all business. I even cleared my throat before starting. I opened with the religious reasons: “First of all, Islam teaches us that we are meant to learn all our lives. From the cradle to the grave.” I was weaving in quotes from the Quran and the hadiths that I’d memorized as supporting evidence. “Both men and women have the same obligations as Muslims. Women have to pray as often as men, they fast for Ramadan, and they go to Mecca on a pilgrimage, so their obligation to learn is the same as that of men. Offering education to girls would enable them to follow the path they’re supposed to, and fulfill their God-given duty.

“Secondly,” I continued, “women are taking care of families, and the better educated they are, the better they can do that.” There was a story my mother told me a long time ago, about a woman from her family who accidentally poisoned her baby boy by giving him powdered glue instead of formula. The containers looked the same and she didn’t know how to read. Her boy ended up in the hospital for three days. He recovered in the end, but she never got over almost killing her son. Teaching women like her how to read, teaching them the basics of first aid, would help them to manage the household better. “It would keep the families and our community safer.

“Lastly, the more the women know, the more they can teach their children. By educating girls, you’re educating boys, too. These girls will become mothers. And educated mothers can teach their children, both girls and boys. Women are the key to educating the entire family.” I insisted on highlighting the role of a mother for a good reason. The mother is the first and the last woman an Afghan man listens to.

See? All for the benefit of the community.

Having run out of breath, I stopped as abruptly as I started. It didn’t matter, though. We were talking values now. It was content over style. He had enough information to decide.

The old man was hard to read, but I knew he listened closely. He took a painfully long time to react. He offered more tea, then more snacks, while I sat there waiting for him to respond. Maybe I deserved that agony for being unprepared the first time around, but the wait, from where I sat, still seemed unnecessarily cruel.

When he finally called it a “fine idea,” I thought my head would explode.

Improbably, walking away the first time around was the right call. I realized he didn’t see our conversation as a dispute. He wasn’t opposed to educating girls. I wasn’t an enemy; I was a partner. He just needed me to do better.

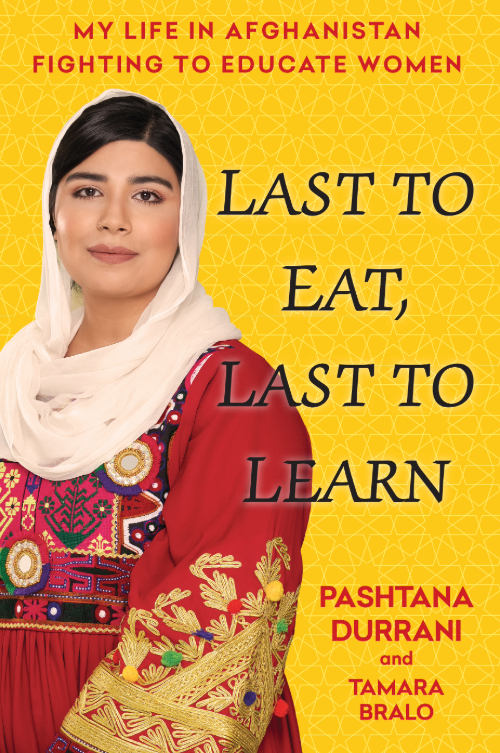

Pashtana Durrani is an International Scholar-in-Residence at the Wellesley Centers for Women. Her book Last to Eat, Last to Learn: My Life in Afghanistan Fighting to Educate Women, co-authored with Tamara Bralo, will be released on February 20, 2024.

Close to half a century has passed since I lived in

Close to half a century has passed since I lived in  But as much as I believed in my work and as much as I loved Colombia—the food, the people, the mountains, majestic and ever changing as clouds and sun played hide and seek—I realized Amy’s physical and developmental challenges required medical care and educational programs unavailable in Colombia. Amy and I left. I was unsure if I would ever return.

But as much as I believed in my work and as much as I loved Colombia—the food, the people, the mountains, majestic and ever changing as clouds and sun played hide and seek—I realized Amy’s physical and developmental challenges required medical care and educational programs unavailable in Colombia. Amy and I left. I was unsure if I would ever return. ote for me. One of the bits of information our guide mentioned as we passed a large public school was that schools were now required to teach sex education to students starting in the early grades. Recalling the opposition our sex education project had encountered years before, I asked if the requirement was enforced or merely a regulation on the books. He smiled. “Well, Senora, I can’t speak for the entire country, but certainly in the big cities and towns it is a regular part of the educational program. The law was passed in 1994.”

ote for me. One of the bits of information our guide mentioned as we passed a large public school was that schools were now required to teach sex education to students starting in the early grades. Recalling the opposition our sex education project had encountered years before, I asked if the requirement was enforced or merely a regulation on the books. He smiled. “Well, Senora, I can’t speak for the entire country, but certainly in the big cities and towns it is a regular part of the educational program. The law was passed in 1994.” A spectacular

A spectacular  all interested in medicine,” we asked. “No, I’m going to study psychology,” another replied.

all interested in medicine,” we asked. “No, I’m going to study psychology,” another replied.

services to women and girls who need them. What our clinic staff has seen firsthand is that blocking access to abortion and comprehensive reproductive health care doesn’t stop them from being needed, or even stop them from happening — it just keeps them from being safe. Due in large part to extensive abortion bans throughout the region, 95% of abortions in Latin America are performed in unsafe conditions that threaten the health and lives of women.

services to women and girls who need them. What our clinic staff has seen firsthand is that blocking access to abortion and comprehensive reproductive health care doesn’t stop them from being needed, or even stop them from happening — it just keeps them from being safe. Due in large part to extensive abortion bans throughout the region, 95% of abortions in Latin America are performed in unsafe conditions that threaten the health and lives of women.

capital. It was witnessing homelessness in her city that inspired her to figure out how she and her family could make a real difference, and her “power of half” principle has since become a movement.

capital. It was witnessing homelessness in her city that inspired her to figure out how she and her family could make a real difference, and her “power of half” principle has since become a movement.

The Commission also stated that the post-2015 development agenda must include gender-specific targets across other development goals, strategies, and objectives -- especially those related to education, health, economic justice, and the environment. It also called on governments to address the discriminatory social norms and practices that foster gender inequality, including early and forced marriage and other forms of violence against women and girls, and to strengthen accountability mechanisms for women's human rights.

The Commission also stated that the post-2015 development agenda must include gender-specific targets across other development goals, strategies, and objectives -- especially those related to education, health, economic justice, and the environment. It also called on governments to address the discriminatory social norms and practices that foster gender inequality, including early and forced marriage and other forms of violence against women and girls, and to strengthen accountability mechanisms for women's human rights.

In my hometown, I see evidence that women are emerging as confident, enthusiastic leaders of technology. Recently, I was at a public meeting for a community group planning the inaugural

In my hometown, I see evidence that women are emerging as confident, enthusiastic leaders of technology. Recently, I was at a public meeting for a community group planning the inaugural

s a precursor to teen dating violence. Schools—where most young people meet, hang out, and develop patterns of social interactions—may be training grounds for domestic violence because behaviors conducted in public may provide license to proceed in private.

s a precursor to teen dating violence. Schools—where most young people meet, hang out, and develop patterns of social interactions—may be training grounds for domestic violence because behaviors conducted in public may provide license to proceed in private. But how do recruiters on the front-end value a varsity credential? Does sports participation in college, for example, offer access to enter a corporate career?

But how do recruiters on the front-end value a varsity credential? Does sports participation in college, for example, offer access to enter a corporate career? Social Justice Dialogue: Eradicating Poverty

Social Justice Dialogue: Eradicating Poverty

I was fortunate, however, that my parents were not desperate for the bride price when I was a growing up. I could have been sold for a cow or a goat. Instead, at age 14, when I was feeling hopeless and working as a barmaid, a wonderful family in Kentucky (who knew one of my cousins from when they had done missionary work years earlier) enabled my return to school by paying my school fees for five years. I went on to earn my college degree before working with organizations that were striving to improve the lives of poor families in Africa.

I was fortunate, however, that my parents were not desperate for the bride price when I was a growing up. I could have been sold for a cow or a goat. Instead, at age 14, when I was feeling hopeless and working as a barmaid, a wonderful family in Kentucky (who knew one of my cousins from when they had done missionary work years earlier) enabled my return to school by paying my school fees for five years. I went on to earn my college degree before working with organizations that were striving to improve the lives of poor families in Africa.

We have waited too long! In 1994, governments agreed to an ambitious

We have waited too long! In 1994, governments agreed to an ambitious

institutional changes. Until then, it is largely up to mentors to influence the capable and powerful young women who may otherwise slip through the (huge) cracks.

institutional changes. Until then, it is largely up to mentors to influence the capable and powerful young women who may otherwise slip through the (huge) cracks.