Over the past few years, you may have read about the crisis in youth mental health. In October 2021, the American Academy of Pediatrics declared a national emergency in child and adolescent mental health, and in December 2021, the U.S. surgeon general highlighted the urgent need to address the nation’s youth mental health crisis. Just this month, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended screening for depression in adolescents aged 12 to 18.

October is National Depression and Mental Health Screening Month, so we’d like to highlight one of the tools WCW has been using to approach the youth mental health crisis that is in line with that recommendation: school-based mental health screenings.

Mood Check, our program, partners with schools to screen all students in designated grades and offers additional support to adolescents at high risk for depression and/or suicidal behaviors. We have a multi-pronged approach: We offer resources that increase the school community’s mental health awareness and literacy, which serves as a prevention tool. Then we provide two-level screening for students, including universal, self-reported screening for all students followed by in-depth interviews with students who are identified as high risk. We communicate with parents and guardians about youth depression and resources, and provide more significant follow-up (both immediate and long-term) for parents and guardians of high-risk teens. Finally, we offer referral access for all school families who need to find a mental health professional to help their teen moving forward.

This past school year, we screened a total of 2,078 middle and high school students in the greater Boston area for both depression and anxiety. We met one-on-one with 646 students (about 31%); 237 students (about 11%) revealed to us that they had current or past thoughts of suicide, and 57 students reported that they revealed suicidal thinking or behavior to an adult for the first time when meeting with a clinician on our team. For those who reported suicidal thinking/behavior, we introduced safety plans: a way to identify warning signs, internal coping strategies, supportive people and places, how to make the environment safe, and a motivator for living, along with providing the Suicide Prevention Lifeline phone number. Students retained a copy of the plan that they could reference themselves and/or share with parents, providers, or trusted adults.

A review of our data over time suggests that Mood Check is associated with decreased depressive symptoms in at-risk adolescents and may encourage families to seek treatment for students we identify. This kind of success in a school setting is in line with other research, which shows that teens prefer to receive mental health services in schools, rather than in mental health specialty settings. Anecdotally, we’ve found that teens are more willing to speak with us, because they know they won’t see us again; it can be easier to tell the truth to a stranger than to a parent, teacher, or guidance counselor. We’re glad to provide that listening ear for them.

School screenings alone cannot solve the crisis in youth mental health. But they are an important tool to be used in combination with depression prevention efforts and expanded access to treatment. Our goal is for more teens to be able to get the help they need in order to live healthier and happier lives.

Tracy R. G. Gladstone, Ph.D., is research director, an associate director and a senior research scientist at the Wellesley Centers for Women, where she leads the Depression Prevention Research Initiative.

Sex education in the American public school system varies from state to state and from school district to school district. The lack of standardized sex education makes family education and conversations about sex and relationships all the more important for teenagers and their development. It is often assumed that parents are the default—that they are the only family members responsible for initiating these conversations. In my research conducted with WCW Senior Research Scientist

Sex education in the American public school system varies from state to state and from school district to school district. The lack of standardized sex education makes family education and conversations about sex and relationships all the more important for teenagers and their development. It is often assumed that parents are the default—that they are the only family members responsible for initiating these conversations. In my research conducted with WCW Senior Research Scientist  The pandemic has altered family life in unexpected ways.

The pandemic has altered family life in unexpected ways.  A recent

A recent  As a country we seem to be moving far away from the nurturing and sustaining activity of the settlement houses of our past. The first settlement house, established in New York City’s Lower East Side – Neighborhood Guild – was founded by Stanton Coit, and just a few years later came Hull House in Chicago, materializing through the passionate vision of Jane Addams. Settlement houses were the cornerstone of communities as they over time took on the task of educating citizens, providing English language classes for immigrants, organizing employment connections, and offering enrichment and recreation opportunities to all in the neighborhood. A most significant beginning to the current child and youth development field, settlement houses provided childcare services for the children of working mothers. The Immigrants’ Protective League, The Juvenile Protective Association, The Institute for Juvenile Research, The Federal Children’s Bureau, along with Child Labor Laws can all trace back to the persistent national

As a country we seem to be moving far away from the nurturing and sustaining activity of the settlement houses of our past. The first settlement house, established in New York City’s Lower East Side – Neighborhood Guild – was founded by Stanton Coit, and just a few years later came Hull House in Chicago, materializing through the passionate vision of Jane Addams. Settlement houses were the cornerstone of communities as they over time took on the task of educating citizens, providing English language classes for immigrants, organizing employment connections, and offering enrichment and recreation opportunities to all in the neighborhood. A most significant beginning to the current child and youth development field, settlement houses provided childcare services for the children of working mothers. The Immigrants’ Protective League, The Juvenile Protective Association, The Institute for Juvenile Research, The Federal Children’s Bureau, along with Child Labor Laws can all trace back to the persistent national

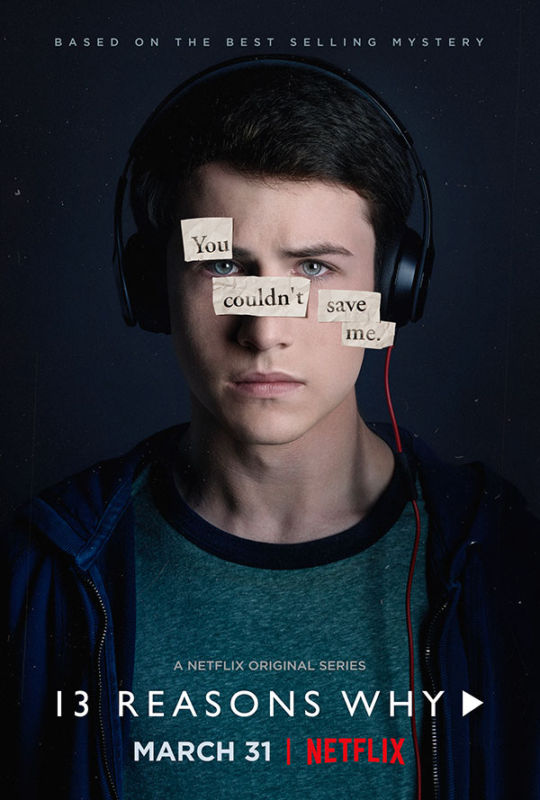

Likewise, we worry about teens that exhibit signs of suicide. Sometimes these signs are subtle, such as giving away prized possessions, withdrawing from friends, or exhibiting significant behavioral changes, such as intense fights with family and friends. Teens thinking about suicide may also provide verbal cues, such as, “I wish I were dead” and “It’s not worth it anymore.” Also, many people who contemplate suicide do so because they believe they are a burden to others, and that they will be doing others a favor if they are no longer here. Thus, if you hear a teen say, “My family would be better off without me,” it is important to take action. Remember that 50-70 percent of people who make a suicide attempt communicate their intent prior to acting, mostly through such actions or verbal cues. Thus, if you recognize any of these signs, it is important to ASK. Although many of us find it scary to ask about suicide, or worry that asking about suicide will give someone the idea to attempt suicide, we know from numerous studies that talking about suicide will not lead to suicidal behavior.

Likewise, we worry about teens that exhibit signs of suicide. Sometimes these signs are subtle, such as giving away prized possessions, withdrawing from friends, or exhibiting significant behavioral changes, such as intense fights with family and friends. Teens thinking about suicide may also provide verbal cues, such as, “I wish I were dead” and “It’s not worth it anymore.” Also, many people who contemplate suicide do so because they believe they are a burden to others, and that they will be doing others a favor if they are no longer here. Thus, if you hear a teen say, “My family would be better off without me,” it is important to take action. Remember that 50-70 percent of people who make a suicide attempt communicate their intent prior to acting, mostly through such actions or verbal cues. Thus, if you recognize any of these signs, it is important to ASK. Although many of us find it scary to ask about suicide, or worry that asking about suicide will give someone the idea to attempt suicide, we know from numerous studies that talking about suicide will not lead to suicidal behavior.

institutional changes. Until then, it is largely up to mentors to influence the capable and powerful young women who may otherwise slip through the (huge) cracks.

institutional changes. Until then, it is largely up to mentors to influence the capable and powerful young women who may otherwise slip through the (huge) cracks.