The 2024 STEAM camps tutors, their host Hon. Adedayo Benjamins-Laniyi, and Ibrahim, at her house in Abuja, Nigeria in July 2024.

The 2024 STEAM camps tutors, their host Hon. Adedayo Benjamins-Laniyi, and Ibrahim, at her house in Abuja, Nigeria in July 2024.Our first science, technology, engineering, art, and mathematics (STEAM) camps, in 2019, gave us opportunities to learn and grow. We brought STEAM kits that included measuring tapes, pipettes, sand timers, test tubes, strings, boxes, and bouncy balls, as well as local materials and products, into communities in Nigeria to teach students STEAM. This has become my passion. A lawyer by vocation, a visiting professor by choice, I found myself in elementary and high school classes ready to learn science in order to be effective in the field with children like I was at that age, 10 to 15—powerless, voiceless, poor, and illiterate.

Fulfilling a dream—I wanted the children to have what I did not have, and so I immersed myself. If I could go from hawking any saleable goods in my village to teaching at Harvard University, then those children could realize their potential to be even better than me. This is also in line with the Convention on the Rights of the Child, Article 31, which states that children of all ages have the right to access and fully participate in cultural and artistic life.

Over the next five years, Dr. Robeson and the Wellesley Centers for Women supplied some of those items for our STEAM camps in Nigeria. It was important to me to ensure that whoever, whatever will add value to my dream was not beyond my reach. For the most part, we did not have the resources, but it never stopped the camps. I acknowledge with gratitude the generous donations from First Parish in Lincoln, Massachusetts. In addition, the director of the University of Rome, Tor, Vergata, Italy, has been instrumental to the work in Nigeria, allowing students from the university to be tutors.

Generally, the students from the University of Rome or elsewhere buy their plane tickets and I provide accommodations, food, and security, with the help of governmental agencies in Nigeria. Students chosen to go must have the ability to adapt, be patient, have empathy for others, possess a nurturing instinct, and be able to be flexible.

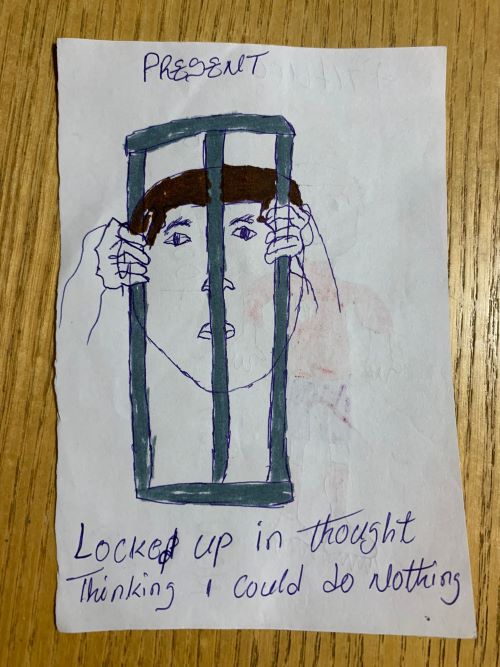

A drawing by a student from one of the 2024 STEAM camps.

A drawing by a student from one of the 2024 STEAM camps.Our previous camps were successful, but the 2024 STEAM camps were exceptional, a game changer. In addition to working with children, we also were able to train teachers from schools and other organizations to continue what we did in the camps.

This past summer we were able to work with children from orphanages, children with disabilities, and others. Our five tutors at the 2024 STEAM camps were Matilde Belleggia, Anna Cascarino, David Marulanda, and Angelica Felici Caravella, all from the University of Rome, Tor, Vergata, Italy, and Silvio Dionisotti from the U.S. These tutors provided intrinsic motivation, enjoyment, and positive attitudes, helped with cognitive problem-solving and self-discipline, developed tools for communication and meaning-making, and fostered creativity and imagination for the children whose communities participated around Abuja, Nigeria and beyond.

Our art teacher, Angelica, was creative in her approach to teaching. She asked the children to draw themselves now, and what they want to be in the future. One of my favorites was the drawing that said, “now I feel I am in a cage, but in the future, I want to be a footballer.” Another was an answer from a pupil that is full of food for thought: In answer to the question of what she wants to be in life, she said “a white girl.” The idea of being white could be a rejection of who she is and that may hinder a few things as she grows up. I told her what matters is the content of her character and not the color of her skin.

The art classes led to the publication of The Children's Artwork, from 2024, Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Mathematics' (STEAM) Camps, published by the University of Rome Press in January 2025.

Hauwa Ibrahim is a Senior International Scholar-in-Residence at the Wellesley Centers for Women. She is an international human rights and Shariah law attorney with significant academic and government experience.

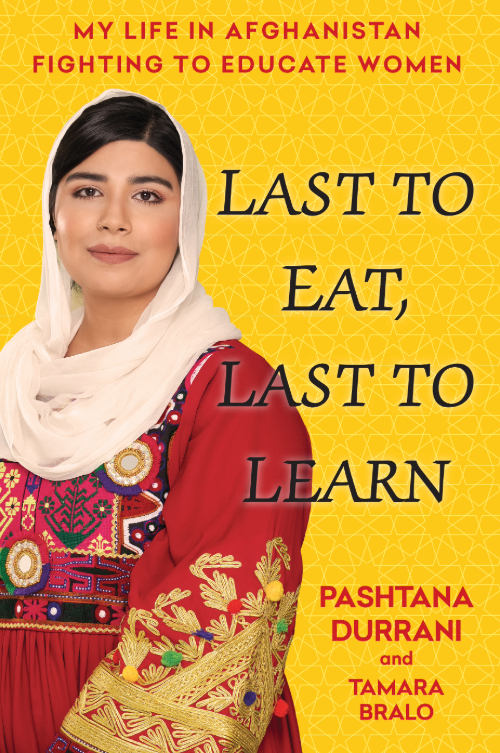

With a collection of government stamps in hand, I now needed to secure the tribal backing for the project. Government approval merely made my NGO official, but without the tribal endorsement, my effort to educate girls would be just another import with a short shelf life.

With a collection of government stamps in hand, I now needed to secure the tribal backing for the project. Government approval merely made my NGO official, but without the tribal endorsement, my effort to educate girls would be just another import with a short shelf life.

, Ph.D., is a research scientist at the Wellesley Centers for Women studying

, Ph.D., is a research scientist at the Wellesley Centers for Women studying

On March 11, 2021, the House of Representatives passed a bill seeking to “create a special education scheme to support deserving students attending public tertiary institutions across Liberia. The Bill is titled “An Act to Create a Special Education Fund to Support and Sustain the Tuition Free Scheme for the University of Liberia, All Public Universities and Colleges’ Program and the Free WASSCE fess for Ninth and Twelfth Graders in Liberia, or the Weah Education Fund (WEF) for short. The bill when enacted into law, will make all public colleges and universities “tuition-free”. The passage of this bill by the Lower House has been met by mixed reactions across the country: young, old, educated, not educated, stakeholders, parents, teachers among others, have all voiced their opinions about this bill. While some are celebrating this purported huge milestone in the education sector, others are still skeptical that this bill may only increase access but not address the structural challenges within the sector. I join forces with the latter, and in this article, I discuss the quality and access concept in our education sector and why quality is important than access. I recommend urgent action to improve quality for learners in K-12.

On March 11, 2021, the House of Representatives passed a bill seeking to “create a special education scheme to support deserving students attending public tertiary institutions across Liberia. The Bill is titled “An Act to Create a Special Education Fund to Support and Sustain the Tuition Free Scheme for the University of Liberia, All Public Universities and Colleges’ Program and the Free WASSCE fess for Ninth and Twelfth Graders in Liberia, or the Weah Education Fund (WEF) for short. The bill when enacted into law, will make all public colleges and universities “tuition-free”. The passage of this bill by the Lower House has been met by mixed reactions across the country: young, old, educated, not educated, stakeholders, parents, teachers among others, have all voiced their opinions about this bill. While some are celebrating this purported huge milestone in the education sector, others are still skeptical that this bill may only increase access but not address the structural challenges within the sector. I join forces with the latter, and in this article, I discuss the quality and access concept in our education sector and why quality is important than access. I recommend urgent action to improve quality for learners in K-12. Sage Carson was raped by a graduate student in her sophomore year of college. In an article for

Sage Carson was raped by a graduate student in her sophomore year of college. In an article for  It is the spring of 2020, and my senior year at Wellesley College is not at all what I imagined it would be like. Before concerns about COVID-19 led

It is the spring of 2020, and my senior year at Wellesley College is not at all what I imagined it would be like. Before concerns about COVID-19 led  A recent family conversation reminded me of my (long-ago!) elementary school experience of learning who my teacher would be in the coming school year. I remember the sense of anticipation – who will be my teacher?.

A recent family conversation reminded me of my (long-ago!) elementary school experience of learning who my teacher would be in the coming school year. I remember the sense of anticipation – who will be my teacher?. Yesterday on route to work my phone exploded with messages from friends and colleagues urging me to, "Turn on NPR right now,” to hear their

Yesterday on route to work my phone exploded with messages from friends and colleagues urging me to, "Turn on NPR right now,” to hear their  Close to half a century has passed since I lived in

Close to half a century has passed since I lived in  But as much as I believed in my work and as much as I loved Colombia—the food, the people, the mountains, majestic and ever changing as clouds and sun played hide and seek—I realized Amy’s physical and developmental challenges required medical care and educational programs unavailable in Colombia. Amy and I left. I was unsure if I would ever return.

But as much as I believed in my work and as much as I loved Colombia—the food, the people, the mountains, majestic and ever changing as clouds and sun played hide and seek—I realized Amy’s physical and developmental challenges required medical care and educational programs unavailable in Colombia. Amy and I left. I was unsure if I would ever return. ote for me. One of the bits of information our guide mentioned as we passed a large public school was that schools were now required to teach sex education to students starting in the early grades. Recalling the opposition our sex education project had encountered years before, I asked if the requirement was enforced or merely a regulation on the books. He smiled. “Well, Senora, I can’t speak for the entire country, but certainly in the big cities and towns it is a regular part of the educational program. The law was passed in 1994.”

ote for me. One of the bits of information our guide mentioned as we passed a large public school was that schools were now required to teach sex education to students starting in the early grades. Recalling the opposition our sex education project had encountered years before, I asked if the requirement was enforced or merely a regulation on the books. He smiled. “Well, Senora, I can’t speak for the entire country, but certainly in the big cities and towns it is a regular part of the educational program. The law was passed in 1994.” A spectacular

A spectacular  all interested in medicine,” we asked. “No, I’m going to study psychology,” another replied.

all interested in medicine,” we asked. “No, I’m going to study psychology,” another replied.

Although these are all big questions, I have at least learned a few things over the years through my

Although these are all big questions, I have at least learned a few things over the years through my  Lisa Fortuna

Lisa Fortuna

Championship, was confused when he arrived on campus. His

Championship, was confused when he arrived on campus. His

ck History Month, which began as Negro History Week in 1926. He was an erudite and meticulous scholar who obtained his B.Litt. from Berea College, his M.A. from the University of Chicago, and his doctorate from Harvard University at a time when the pursuit of higher education was extremely fraught for African Americans. Because he made it his mission to collect, compile, and distribute historical data about Black people in America, I like to call him “the original #BlackLivesMatter guy.” His self-declared dual mission was to make sure the African-Americans knew their history and to insure the place of Black history in mainstream U.S. history. This was long before Black history was considered relevant, even thinkable, by most white scholars and the white academy. In fact, he writes in the preface of The Negro in Our History that he penned the book for schoolteachers so that Black history could be taught in schools—and this, just in time for the opening of Washington High School.

ck History Month, which began as Negro History Week in 1926. He was an erudite and meticulous scholar who obtained his B.Litt. from Berea College, his M.A. from the University of Chicago, and his doctorate from Harvard University at a time when the pursuit of higher education was extremely fraught for African Americans. Because he made it his mission to collect, compile, and distribute historical data about Black people in America, I like to call him “the original #BlackLivesMatter guy.” His self-declared dual mission was to make sure the African-Americans knew their history and to insure the place of Black history in mainstream U.S. history. This was long before Black history was considered relevant, even thinkable, by most white scholars and the white academy. In fact, he writes in the preface of The Negro in Our History that he penned the book for schoolteachers so that Black history could be taught in schools—and this, just in time for the opening of Washington High School. women. It enlivens my curiosity to imagine my grandmother Jannie as a young woman learning in school about her own history from Carter G. Woodson’s text, which, at that time was still relatively new, alongside anything else she might have been learning. It saddens me to reflect on the fact that my own post-desegregation high school education, AP History and all, offered no such in-depth overview of Black history, African American or African.

women. It enlivens my curiosity to imagine my grandmother Jannie as a young woman learning in school about her own history from Carter G. Woodson’s text, which, at that time was still relatively new, alongside anything else she might have been learning. It saddens me to reflect on the fact that my own post-desegregation high school education, AP History and all, offered no such in-depth overview of Black history, African American or African. After finishing high school, my grandmother Jannie, like many of her generation, worked as a domestic for many years. However, after spending time working in the home of a doctor, she was encouraged and went on to become a licensed practical nurse (LPN), which took two more years of night school. From that point until her death, she worked as a private nurse to aging wealthy Atlantans. This enabled her to make a good, albeit humble, livelihood for herself and her two daughters, along with my great grandmother Laura, who lived with her and served as her primary source of childcare, particularly after her brief marriage to my grandfather, an older man who she found to be overbearing, ended. With this livelihood, she was able to put both her daughters through Spelman College, the nation’s leading African American women’s college, then and now. It stands as a point of pride to our whole family that, although she was unable to attend due to family responsibilities, Jannie herself was also at one time admitted to

After finishing high school, my grandmother Jannie, like many of her generation, worked as a domestic for many years. However, after spending time working in the home of a doctor, she was encouraged and went on to become a licensed practical nurse (LPN), which took two more years of night school. From that point until her death, she worked as a private nurse to aging wealthy Atlantans. This enabled her to make a good, albeit humble, livelihood for herself and her two daughters, along with my great grandmother Laura, who lived with her and served as her primary source of childcare, particularly after her brief marriage to my grandfather, an older man who she found to be overbearing, ended. With this livelihood, she was able to put both her daughters through Spelman College, the nation’s leading African American women’s college, then and now. It stands as a point of pride to our whole family that, although she was unable to attend due to family responsibilities, Jannie herself was also at one time admitted to  ge. Sadly, she didn’t live to see me attain my Ph.D., but, when she passed away, I was already pursuing my Masters degree, and, like her, I was also mother to a second child. Thus, when I inherited The Negro in Our History, it was more than a quaint artifact of an earlier era, and more than just a physical symbol of Black History Month. Rather, it was where Black history, women’s history, the pursuit of education, the pursuit of social justice, my own history, and my own destiny met.

ge. Sadly, she didn’t live to see me attain my Ph.D., but, when she passed away, I was already pursuing my Masters degree, and, like her, I was also mother to a second child. Thus, when I inherited The Negro in Our History, it was more than a quaint artifact of an earlier era, and more than just a physical symbol of Black History Month. Rather, it was where Black history, women’s history, the pursuit of education, the pursuit of social justice, my own history, and my own destiny met.

It’s important to talk with teens before they have sex. Research tells us that it is critical for teens to learn about sexual issues from a trusted adult before they have sex.

It’s important to talk with teens before they have sex. Research tells us that it is critical for teens to learn about sexual issues from a trusted adult before they have sex. capital. It was witnessing homelessness in her city that inspired her to figure out how she and her family could make a real difference, and her “power of half” principle has since become a movement.

capital. It was witnessing homelessness in her city that inspired her to figure out how she and her family could make a real difference, and her “power of half” principle has since become a movement.

Jen Dirga

Jen Dirga Sallie Dunning

Sallie Dunning

In my hometown, I see evidence that women are emerging as confident, enthusiastic leaders of technology. Recently, I was at a public meeting for a community group planning the inaugural

In my hometown, I see evidence that women are emerging as confident, enthusiastic leaders of technology. Recently, I was at a public meeting for a community group planning the inaugural  Social Justice Dialogue: Leadership for Social Change

Social Justice Dialogue: Leadership for Social Change Second, the PPLA explores ways to do teaching and research that is driven by our values. We focus on the kinds of leadership and collective capacity we need to meet the common challenges our society face in a just way. We insist upon rigor and methodological soundness in our work, but we cannot separate moral and ethical considerations from our research and writing. Many scholars believe that our values suffuse our classrooms, laboratories, articles, and books whether we recognize and foreground them or not. The Project on Public Leadership seeks ways to affirm and support explicitly values-driven work.

Second, the PPLA explores ways to do teaching and research that is driven by our values. We focus on the kinds of leadership and collective capacity we need to meet the common challenges our society face in a just way. We insist upon rigor and methodological soundness in our work, but we cannot separate moral and ethical considerations from our research and writing. Many scholars believe that our values suffuse our classrooms, laboratories, articles, and books whether we recognize and foreground them or not. The Project on Public Leadership seeks ways to affirm and support explicitly values-driven work.

s a precursor to teen dating violence. Schools—where most young people meet, hang out, and develop patterns of social interactions—may be training grounds for domestic violence because behaviors conducted in public may provide license to proceed in private.

s a precursor to teen dating violence. Schools—where most young people meet, hang out, and develop patterns of social interactions—may be training grounds for domestic violence because behaviors conducted in public may provide license to proceed in private.

Students are always watching. They are watching adults at their best and they are particularly watching adults when they are in conflict. While emphasis and expectations of behavior is often placed on the students, adults in schools should remember to take a step back and look at themselves, their relationships, and the behaviors students see them model. It’s imperative that adult communities in schools reflect the same expectations of behavior that we have for students. Otherwise a climate may develop where students and adults may not feel safe to identify, report, and effectively address bullying behavior.

Students are always watching. They are watching adults at their best and they are particularly watching adults when they are in conflict. While emphasis and expectations of behavior is often placed on the students, adults in schools should remember to take a step back and look at themselves, their relationships, and the behaviors students see them model. It’s imperative that adult communities in schools reflect the same expectations of behavior that we have for students. Otherwise a climate may develop where students and adults may not feel safe to identify, report, and effectively address bullying behavior.

All day I wondered how the class had responded to the film. I was worried, but the description of the discussion surpassed my expectations. I called the teacher to thank her. She said that they had been working on stereotypes and biases for several weeks but it wasn’t until kids who were classmates talked about their own experience that opinions and attitudes shifted. This was before standardized testing and she was a brilliant teacher who made time for this important discussion. I know there are many brilliant teachers who could create spaces for tolerance in their classrooms if given some tools and language to guide them.

All day I wondered how the class had responded to the film. I was worried, but the description of the discussion surpassed my expectations. I called the teacher to thank her. She said that they had been working on stereotypes and biases for several weeks but it wasn’t until kids who were classmates talked about their own experience that opinions and attitudes shifted. This was before standardized testing and she was a brilliant teacher who made time for this important discussion. I know there are many brilliant teachers who could create spaces for tolerance in their classrooms if given some tools and language to guide them. Social Justice Dialogue: Eradicating Poverty

Social Justice Dialogue: Eradicating Poverty I was fortunate, however, that my parents were not desperate for the bride price when I was a growing up. I could have been sold for a cow or a goat. Instead, at age 14, when I was feeling hopeless and working as a barmaid, a wonderful family in Kentucky (who knew one of my cousins from when they had done missionary work years earlier) enabled my return to school by paying my school fees for five years. I went on to earn my college degree before working with organizations that were striving to improve the lives of poor families in Africa.

I was fortunate, however, that my parents were not desperate for the bride price when I was a growing up. I could have been sold for a cow or a goat. Instead, at age 14, when I was feeling hopeless and working as a barmaid, a wonderful family in Kentucky (who knew one of my cousins from when they had done missionary work years earlier) enabled my return to school by paying my school fees for five years. I went on to earn my college degree before working with organizations that were striving to improve the lives of poor families in Africa. Social Justice Dialogue:

Social Justice Dialogue:  Eric Bettinger and his colleagues

Eric Bettinger and his colleagues

During the flight home, as I reviewed the day’s

During the flight home, as I reviewed the day’s

According to Benard, “we are all born with innate resiliency, with the capacity to develop the traits commonly found in resilient survivors: social competence (responsiveness, cultural flexibility, empathy, caring, communication skills, and a sense of humor); problem-solving (planning, help-seeking, critical and creative thinking); autonomy (sense of identity, self-efficacy, self-awareness, task-mastery, and adaptive distancing from negative messages and conditions); and a sense of purpose and belief in a bright future (goal direction, educational aspirations, optimism, faith, and spiritual connectedness)” (Benard, 1991).

According to Benard, “we are all born with innate resiliency, with the capacity to develop the traits commonly found in resilient survivors: social competence (responsiveness, cultural flexibility, empathy, caring, communication skills, and a sense of humor); problem-solving (planning, help-seeking, critical and creative thinking); autonomy (sense of identity, self-efficacy, self-awareness, task-mastery, and adaptive distancing from negative messages and conditions); and a sense of purpose and belief in a bright future (goal direction, educational aspirations, optimism, faith, and spiritual connectedness)” (Benard, 1991).

prone to anxious feelings or those with their own trauma history can be triggered by another traumatic event, even if it did not directly happen to them. In addition to the positive, supportive classroom climate and the social and emotional learning tools that Open Circle provides, some students may need additional time with a school psychologist or guidance counselor to help them manage their fears.

prone to anxious feelings or those with their own trauma history can be triggered by another traumatic event, even if it did not directly happen to them. In addition to the positive, supportive classroom climate and the social and emotional learning tools that Open Circle provides, some students may need additional time with a school psychologist or guidance counselor to help them manage their fears.